“Ku’damm 59”: Life lies under lipstick

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

And when do they sing now? In the new episodes of “Ku’damm 59,” the backdrop of the ideal world is first staged and then lustily scrapped.

Oh, it could be so beautiful, this sentence, a thank-you for all the privations of a single woman with three daughters. But it isn’t. “Mutti, you can really always be counted on,” is the bitter observation of the youngest daughter Monika, who stands soaked, heavily pregnant and homeless at the door and is turned away by the lady of the house with her back pressed through and cold friendliness, because it’s the fifties and “I can’t make a mockery of myself.”

Over large parts the three episodes remind of candy-colored cinema dreams from the fifties

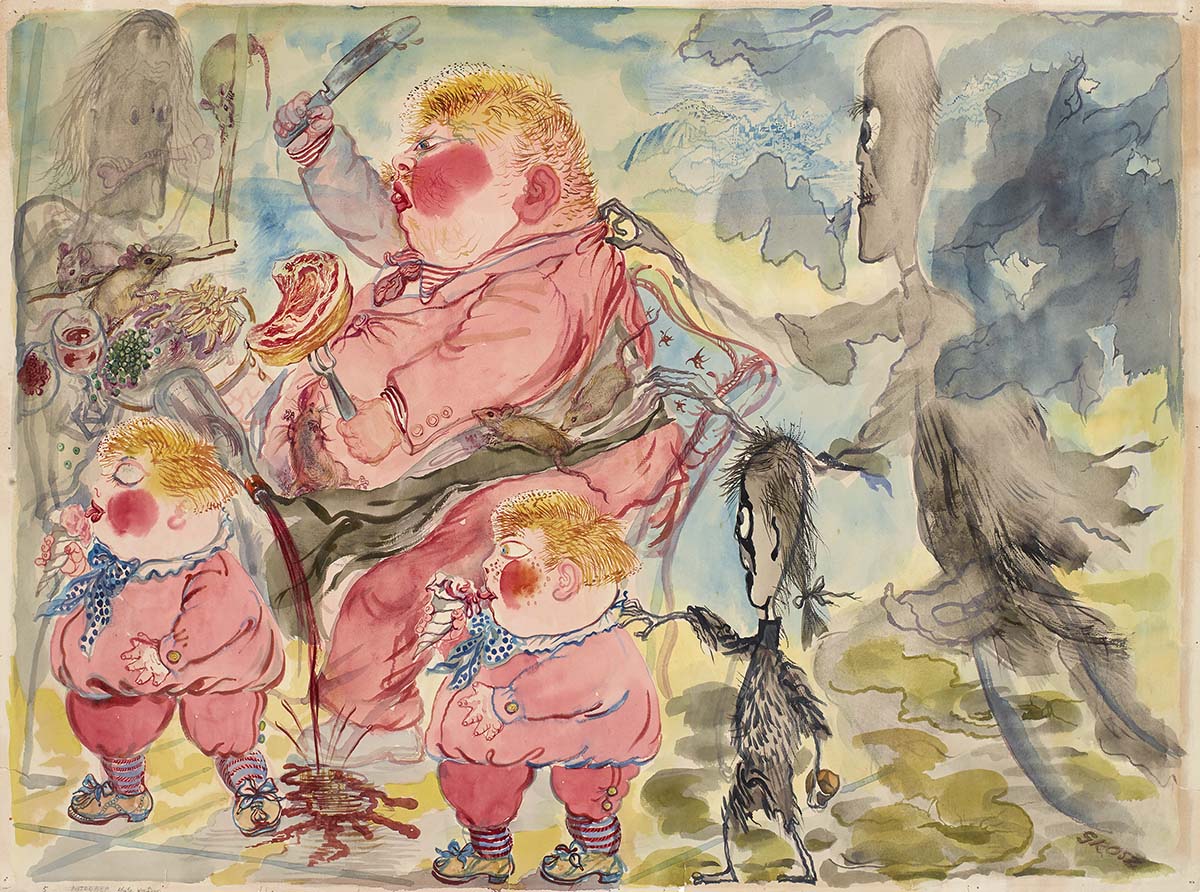

Yes, we could already rely on Mutti in the multi-part series Ku’damm 56, in which we got to know the Schöllack household of women in the Berlin dance school “Galant” two years ago on ZDF, with their daughters Helga, Eva and the headstrong Monika. And Mutti remains completely herself in the sequel Ku’damm 59, set three years later: a dragon-like chaperone with her secret weakness for the time with the Führer, a somewhat garish chic and loud life lies energetically covered up in high heels. Like the one about her daughters’ father not having left her, but having been killed in the war.

Claudia Michelsen plays this Caterina Schöllack masterfully as an all-time lipstick-armed strategist of social advancement who passes off her relentlessness as motherly love. With her play, even in the sequel, she almost single-handedly provides the period primer of pseudo-morality against which the daughters plunge into happiness or unhappiness, the one easily confused with the other. That the marriage of the pretty Helga does not lead directly to domestic happiness was already suspected in the first season; in the second, thanks to maternal intrigues, she now raises Monika’s child and finally even becomes pregnant herself. But her husband Wolfgang will fall in love, forbiddenly with an irresistible lawyer.

Ku’damm 59 is about the fact that life may have to be quite different. That as a daughter, according to the mother dragon, you have to throw yourself into misfortune in order to possibly become happy. But the multi-part series, which already made its appeal in the first season, is set up as a grand narrative about the emancipation of the young generation in post-war Germany, as a process of self-discovery despite evil role expectations for women, sadistic rules of decency and the whole past that no one talks about. It all gets a bit more serious and existential in the second part.

But the beauty of Ku’damm is that the film (and actress Michelsen) allows the dragon Caterina her moments fed by a glass of “women’s gold” and occasionally a secret longing. And so this time, to compensate for the very harsh reality, Caterina Schöllack is allowed to find happiness in a man entirely to her liking; or shall we say: a corner of it.

Perhaps it must be briefly explained at this point that neither Caterina nor Eva or Helga are the real heroines of Ku’damm. The real center is Monika (Sonja Gerhardt), the impossible daughter who just can’t fit in and has the wrong friends, namely a dubious Freddy who lives in a condemned building and calls her “Monikind” and says “Without you there would be no me at all.” Freddy always has the fag in his mouth and a number tattooed on his arm, that’s the number of the good Lord, he says casually to the cute girls when they ask, and that’s enough for them. With her boyfriend Freddy, Monika learned rock ‘n’ roll and fathered the little child. Even though her great pale love is the angry industrialist’s son Joachim Franck (Sabin Tambrea).

And then? Then screenwriter Annette Hess (directed by Sven Bohse) had the rather ingenious idea of having Freddy and Monika stumble into a film career.

In general, Ku’damm 59 itself resembles a candy-colored cinema dream from the late fifties so much that you think: And when are they going to sing? The film is shot as a film within a film, something with Schlager in dirndl and lederhosen, as once in Im Weißen Rößl. Monika buys a chic convertible from the money, and Mutti Schöllack finds a kindred spirit in director Kurt Moser, who made films for the people’s sensibilities until 1944, as he says, and now makes entertainment. Ulrich Noethen is allowed to be wonderfully Austrian and a really lousy groper, but these wonderfully mendacious settings of the ideal world are then scrapped again just as lustily as they are built up here by the opulent set.

For unlike the hit movie dreams, the Schöllack saga also shows the other German reality. Shame-ridden and punishable homosexuality; the legal power of husbands over their wives; and Freddy makes acquaintance with a prosecutor who is preparing an Auschwitz trial, as Fritz Bauer really did in Frankfurt from 1963 on. In the truest moments, however, Mutti and her daughters sit together at the table, united in their respective defeats, and one suspects that the four women here really do not need a man to survive.